Introduction

In the shadow of Europe's empires, a Haitian intellectual dismantled the pseudoscience of racial hierarchy and reframed the meaning of human equality. Anténor Firmin's life and work still challenge the 21st‑century conscience.

The Forgotten Giant of Anthropology

Born on October 18, 1850, in Cap‑Haïtien, Firmin emerged from the world's first Black republic to confront an entrenched ideology: that humanity could be ranked by race. His groundbreaking 1885 book, De l'égalité des races humaines (The Equality of the Human Races), dismantled the scaffolding of scientific racism and offered a radical new vision of human unity.

At a time when European and American scholars used craniology, phrenology, and selective archaeology to justify colonialism and slavery, Firmin stood as a lone voice of rigorous counter-argument. He challenged the very foundations of racial pseudoscience, demonstrating through careful analysis that differences among human populations were products of environment, history, and culture - not innate biological hierarchy.

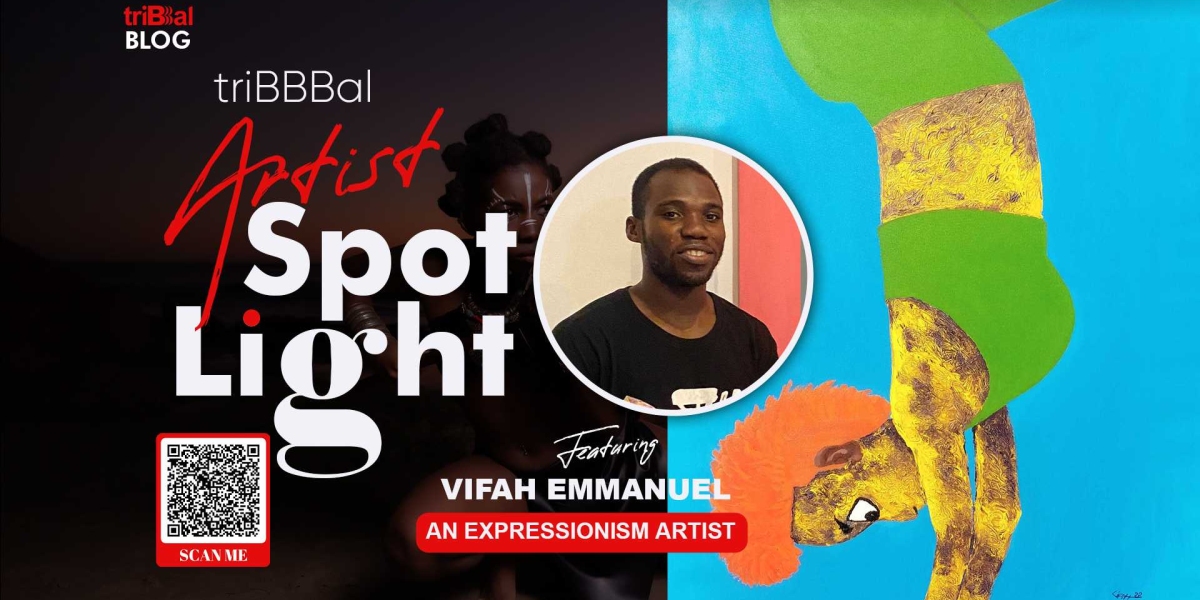

Hero portrait: Firmin set against Haiti's blue‑red palette with echoes of Paris and Cap‑Haïtien.

A Haitian Mind in the Age of Empire

Shaped by the ideals of independence and the educational tradition of northern Haiti, Firmin rose through public service - Inspector of Schools, a seat in the Chamber of Representatives, and later a diplomatic post in Paris. In France, he encountered the intellectual battleground where race science cloaked prejudice in academic garb.

The late 19th century was an era of aggressive colonial expansion, justified by theories of racial superiority. In this context, Firmin's presence in Paris was itself a political statement. As a Black diplomat and intellectual from Haiti - the nation born of the world's only successful slave revolution - he embodied a living refutation of European claims about racial capacity and civilization.

Origins: a cinematic evocation of Cap‑Haïtien's streets and shoreline in the 19th century.

Paris: A Counter‑Revolution of Ideas

Amid the Anthropological Society of Paris, Firmin heard arguments from figures influenced by Arthur de Gobineau's Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races. Rather than retreat, he responded with a rigorous counter‑thesis: there are no inferior races - only unequal conditions. Using comparative anatomy, linguistics, and archaeology, he inverted the paradigm.

Firmin's methodology was revolutionary. He applied the same empirical standards that European scientists claimed to use, but without their prejudicial assumptions. He examined Egyptian civilization, African kingdoms, and indigenous American cultures, demonstrating that technological and cultural achievements were universal human capacities, not racial endowments. His work predated Franz Boas's cultural anthropology by decades, yet remained largely unknown outside Francophone circles.

In the arena of ideas: a Paris lecture hall where Firmin's positive anthropology took shape.

"If Europe produces philosophers, then Africa has produced kings and builders.Civilization is a garden watered by many streams."

Science as a Tool of Liberation

Firmin called his method anthropologie positive - positive anthropology. Decades before Boas, he insisted that culture - not race - is the foundation of human difference. Knowledge must serve justice, not prejudice. This was not merely an academic position; it was a moral and political stance that challenged the entire edifice of colonial ideology.

His book systematically dismantled the claims of racial science. He critiqued the misuse of cranial measurements, exposed the circular reasoning in theories of racial hierarchy, and demonstrated that historical inequalities resulted from conquest, exploitation, and unequal access to resources—not from inherent differences in human capacity. In doing so, he laid the groundwork for modern anti-racist scholarship.

Pages that changed the frame: De l'égalité des races humaines amid the tools of inquiry.

Haiti's Intellectual Ambassador

For Firmin, Haiti held a global mission: to be a moral force in an era of empire. His 1902 presidential campaign championed education, competence, and administrative reform - blueprints for national renewal that later reformers would echo. Though he lost the election, his vision for Haiti as a beacon of Black achievement and universal human dignity continued to inspire generations.

Firmin believed that Haiti's success or failure would be interpreted as evidence for or against the capacity of Black people for self-governance. This placed an enormous burden on the young nation, but also gave its intellectuals and leaders a sense of profound historical responsibility. Firmin dedicated his life to ensuring that Haiti would fulfill its revolutionary promise.

Beacon nation: Haiti's shoreline rendered as a symbol of liberty and leadership.

Exile, Reflection, and St. Thomas

After political upheaval, Firmin lived in exile in St. Thomas, continuing to write until his death in 1911. The wider world would rediscover him only later - through Pan‑Africanism, Négritude, and postcolonial studies. In exile, he remained

intellectually active, corresponding with scholars and continuing to advocate for Haiti's place in the world.

His final years were marked by a poignant combination of isolation and continued intellectual vitality. Though separated from his homeland, Firmin never ceased to think and write about the future of Haiti and the broader struggle for racial justice. His exile became a metaphor for the marginalization of Black intellectuals in the global academy—a situation that persists, in different forms, to this day.

Exile and horizon: St. Thomas at twilight - quiet, resolute, and forward‑looking.

The Legacy of a Revolutionary Mind

Firmin's ideas anticipated the humanistic anthropology and global rights frameworks of the 20th and 21st centuries. Today he stands as a pioneer of anti‑racist science and one of Haiti's most enduring voices. His work has been rediscovered by scholars of African diaspora studies, postcolonial theory, and the history of anthropology.

Contemporary movements for racial justice, decolonization, and epistemic diversity owe an unacknowledged debt to Firmin. His insistence that knowledge production must be accountable to ethical principles, and that science cannot be separated from its social consequences, resonates powerfully in our current moment. As we confront ongoing legacies of racism and colonialism, Firmin's voice speaks with renewed urgency.

Living inheritance: a collage of students, scholars, and archives carrying Firmin's work forward.

Key Themes

- Early, rigorous critique of scientific racism: Firmin challenged racial pseudoscience decades before it became academically mainstream to do so.

- Positive anthropology: Culture, not race, as the source of human difference - a foundational principle of modern anthropology.

- Haiti as a moral and intellectual beacon: The first Black republic carried a global responsibility to demonstrate Black achievement.

- Legacy across Pan‑Africanism, Négritude, and decolonial thought: Firmin's ideas influenced generations of Black intellectuals and anti-colonial movements.

About Anténor Firmin

Born: October 18, 1850

Location: Cap‑Haïtien, Haiti

Died: September 19, 1911

Location: St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands

Notable Work:

De l'égalité des races humaines (1885)

The Equality of the Human Races

"Human beings are all the same... endowed with the same qualities anddefects."

— Anténor Firmin

Suggested Citation

Pierre‑Louis, L. (2025). Anténor Firmin: The Haitian Visionary Who Reimagined Humanity. triBBBal Digital Magazine.

Image Credits

All images are AI-generated cinematic graphics designed specifically for this article at 4K resolution (3840×2160). Alt text and captions included for accessibility.

Production Notes

This digital feature combines historical scholarship with contemporary web design to honor Firmin's legacy. Each visual element has been carefully crafted to evoke the dignity and intellectual power of his work.

Design Elements:

- Color palette inspired by Haiti's blue and red flag

- Classic serif typography for scholarly readability

- Cinematic 16:9 imagery with documentary aesthetics

- Responsive layout optimized for all devices

- Accessibility-first approach with semantic HTML

Further Reading

To learn more about Anténor Firmin and his contributions to anthropology and antiracist thought, consult academic databases and specialized collections on Haitian intellectual history.

Article Completed: October 2025

Author: Lortir Pierre-Louis

Subject: Anténor Firmin (1850 – 1911)

Purpose: Educational commemoration of a pioneering intellectual